IMPERIUM: CONSPIRATOR and DICTATOR

Based on the Cicero novels by Robert Harris, adapted by Mike Poulton.

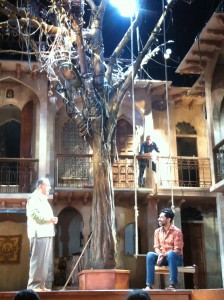

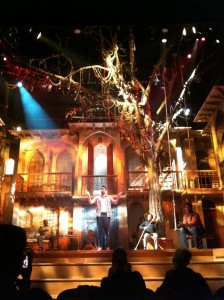

Royal Shakespeare Company, directed by RSC Artistic Director Greg Doran. First performed at the Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon in November 2017. Transferred to London from 14th June.

From Robert Harris’s acclaimed Cicero trilogy of books about politics, sex, murder and oratory – Ancient Rome in a nutshell – we get what is essentially a story told in six new plays across an entire day of theatregoing (or two nights) adapted by Mike Poulton (RSC: Wolf Hall; Bring Up the Bodies). It never feels like a slog though, as each part is split across three acts with two full intervals. That world of over two thousand years ago straddling the Tiber races through time towards us at lightning speed to the present day, with Poulton’s use of modern day vernacular, visual gags referring to Donald Trump and talk of the newly-conquered Britain being just outside Europe reminding us that in politics, nothing ever changes.

The books told the story of Marcus Tullius Cicero, Roman Senator, consul, Father of the Nation and orator, in volumes narrated by his slave and later freed secretary, Tiro. Olivier- and Tony Award-winner Richard McCabe (RSC: Associate Artist; School of Night; King John) leads the cast as Cicero. Tiro is retained in the stage production in this role, our go-between breaking the fourth wall with frequent comic asides. Joseph Kloska (RSC: Measure for Measure) portrays Tiro as earnest, intense and loyal in a finely-tuned performance, at Cicero’s side throughout his adult life.

As the consummate politician and meddler, McCabe imbues Cicero with wit, ingenuity and a self-indulgent streak, but also shows his weaknesses, foibles and mistakes. Desire for a status symbol befitting the Father of the Nation, he buys a house from fellow Senator Crassus (David Nicolle) on the Palatine (from which we derive first the Italian, palazzo, then the English palace). Of course, he’s been played as part of a scheme to discredit him in the later trial of his consular colleague, Hybrida, played by Hywel Morgan (RSC: Queen Anne; The Alchemist).

Julius Caesar, played powerfully by Peter de Jersey, (RSC: Associate Artist; Hamlet; As You Like It) is shown as more rounded a character than usual. We see the uneasy friendship between him and Cicero, which ends when Caesar’s assassins dispatch the dictator, and Cicero denounces him to an uncomfortably sad Tiro – “We were his slaves!”. Before that, we see his return to Rome from conducting his Gallic wars, and his Triumph, where we first meet Octavian. Caesar’s nephew and posthumously adopted son, later to become the Emperor Augustus, is played by Oliver Johnstone (RSC: King Lear; Oppenheimer) with hints of ruthless determination that characterised his later rule. His right-hand man Agrippa, who in real life was later to be responsible for the repair of old aqueducts and a building programme of new ones to supply the expanding city, is a lot more blunt in his dealings with Cicero, mistrusting him.

A standout performance by Joe Dixon (RSC: Associate Artist; Boris Gudonov; The Orphan of Zhao) in the dual roles of Catiline and Marc Anthony ranges from hilarity to terror and anticipation at where he will take both roles.

Siobhán Redmond’s (RSC: Associate Artist; King John; Much Ado About Nothing) turn as Terentia, Cicero’s wife, is not blessed with a lot of stage time. As one of only four actresses in the cast, she probably has the most amongst them. She is variously deeply in love and exceptionally angry with Cicero, when he exiles himself to Brundisium after refusing Caesar’s perfection when the Republic falls for the first time. Terentia is left with his daughter Tullia (Jade Croot, an RSC veteran at age 19) pregnant with her sixth child and dangerously ill.

The aforementioned Trumpian visual gags come in the form of Christopher Saul’s (RSC: King Lear; The Canterbury Tales) Pompey Magnus. With his hair adrift and his self-importance boundless, the reference to the US President fits very nicely. Professor Dame Mary Beard assures us that Pompey indeed had a quiff, so it’s also historically accurate as far as can be determined.

Those with truly expert knowledge of Ancient Rome will find things missing or simplified, as I suspect perhaps in the novels too. Marc Anthony’s marriage to one of Hybrida’s daughters, for example, long before Fulvia and Cleopatra. For almost all of such theatregoers, I believe this will not matter a jot. One is always so present in the drama, swept along by Tiro, that there is no time for fact checking before we move on.

The excellent cast includes Eloise Secker as Clodia and Fulvia; Nicholas Boulton as the augur Metellus Celer and Nicholas Armfield as Clodius. Alisha Williams plays roles including Caesar’s second and third wives Pompeia and Calpurnia.

There is beautiful, evocative and dramatic music – trumpets and drums – by Paul Englishby, movement direction is by Anna Morrissey, (watch for some powerful filmic fight scenes in Part Two with fight director Terry King) lighting is by Mark Henderson and the designer is Anthony Ward, who uses brown brick and grey block to give us the various senatorial meeting places, people’s houses and battlefields with the help of a giant orb above the stage by RSC Production Video.

Until 8th September, Gielgud Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue. rsc.org.uk *****/*****